Part of the Nature’s Architects collection

Termite mounds are renowned for their height, but it’s their internal structure that makes them an impressive build. They are remarkable examples of natural engineering, designed to create a stable internal environment that supports the colony’s survival.

The termite mound’s architecture is built to facilitate airflow, temperature regulation, humidity control and protection from predators and hazards.

The mounds are constructed using a mixture of soil, saliva, and faecal matter, which hardens to form a durable and resilient structure. The internal temperature is maintained at a near constant 30°C, with humidity maintained at 90% or higher.

Mounds hold in heat and humidity, but this causes significant CO2 build up. Hundreds of thousands (potentially millions) of termites respiring, along with fungus cultivation contributes to CO2 production which then can’t escape due to the enclosed space and inefficient diffusion of gases (due to the tunnel networks).

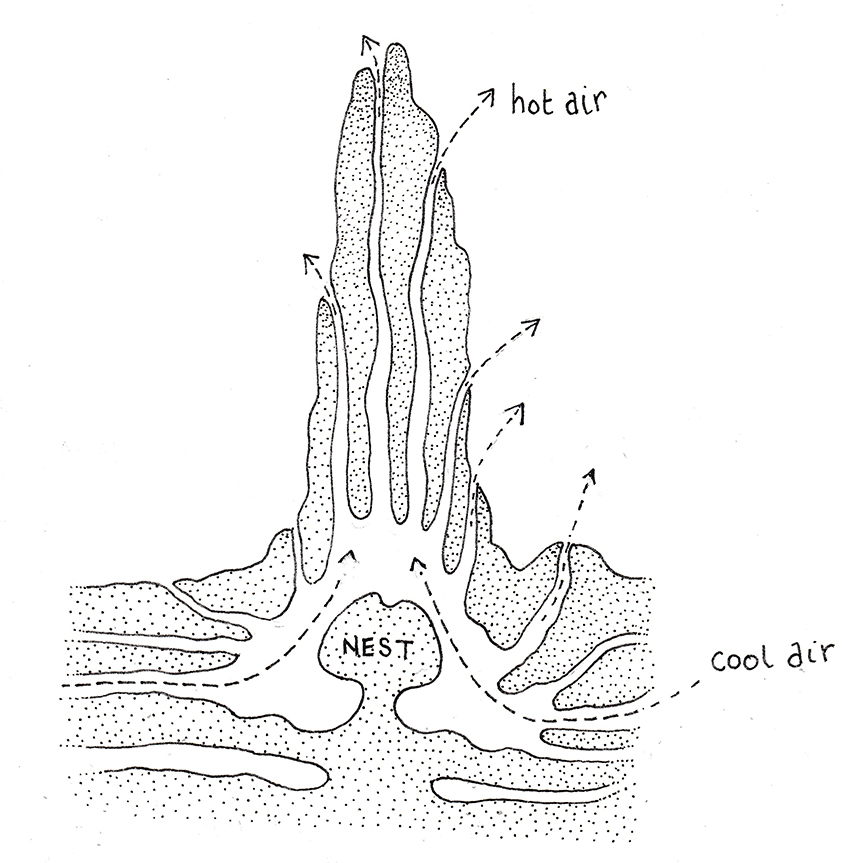

To counter this, the mounds are built with a complex ventilation system of smaller and larger pores in the surface structure which expel excess CO2. Larger pores facilitate direct gas exchange during high winds, while the smaller pores allow continuous diffusion regardless of external weather conditions.

The mound design also promotes the stack effect, where warmer, CO2-rich air rises and exits through upper vents or chimneys. This creates a pressure difference that draws cooler, oxygen-rich air in from lower openings.

The Importance of Humidity

Termite eggs and larvae are prone to desiccation and symbiotic fungi require a moist environmental to survive. As well as that, the material used to build the mound require moisture to maintain their integrity, otherwise they risk becoming dry and brittle.

They maintain the humidity by transferring water-rich soil from deeper underground to different parts of the mound. As evaporation occurs, the moisture content across the mound increases.

The porous mound structure also allows water to move throughout the mound via capillary action. This action also allows water to move from the larger pores to smaller pores and keeps the larger pores open for ventilation. These channels also act like drainage pipes which allows water to flow away from nest chambers to prevent waterlogging.

References

Wei, Y., Lin, Z., Wang, Y., & Wang, X. (2023). Simulation and Optimization Study on the Ventilation Performance of High-Rise Buildings Inspired by the White Termite Mound Chamber Structure. Biomimetics, 8(8), 607.

Korb, J. (2003). Thermoregulation and ventilation of termite mounds. Naturwissenschaften, 90, 212-219.