Ralph Waldo Emerson, the American essayist, once wrote that “life is a perpetual instruction in cause and effect”. I think this sums up the One Health approach, in that changes in the environment affect animal behaviour. This, in turn, affects disease spread. Through considering animal, human and environmental health as one system, we can more accurately predict and control infectious pathogens (Rabinowitz et al. 2013).

Habitat loss leads to outbreaks of Hendra virus

A study by Eby et al. (2023) demonstrates the connection between environment, behaviour and disease. They linked rapid changes in bat behaviour with outbreaks of Hendra virus. These changes in behaviour were a response to food shortages in the environment. During times of winter food shortages, populations break up (population fission). Small groups would roost close to reliable (and usually sub-optimal) food sources in gardens and agricultural areas. When the shortage abated, they would return (population fusion).

From 1996 to 2002, roosting and foraging behaviours were stable and there were no detected spill-overs. Between 1996 and 2018, a third of the winter foraging habitat had been cleared. This was linked with a five-fold increase in roosting sites and 87% of these roosts were in urban areas. From 2006 to 2020, Hendra virus outbreaks increased rapidly. Detection occurred in 80% of the years and in 75% of them, appeared in annual clusters of three or more.

The researchers concluded that habitat loss was causing large numbers of bats to persistently overwinter in agricultural areas. These areas are in close proximity to horses. Having to rely on suboptimal food sources, these bats were also nutritionally stressed which facilitated virus shedding. Pulses of winter-flowering did reduce spillovers by drawing bats into the native forests but these events are becoming increasingly rare.

Land-Use and Emerging Diseases

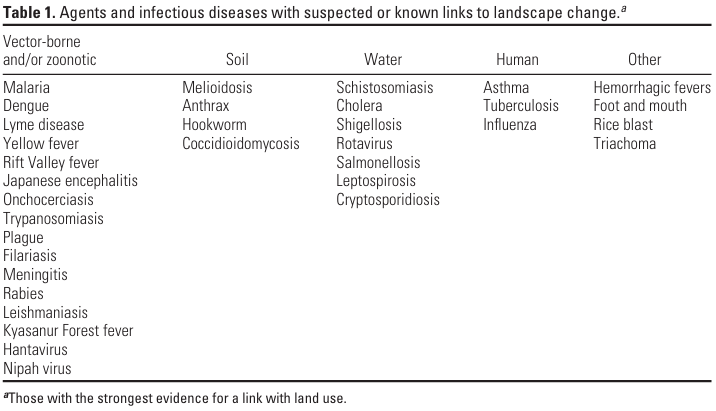

Across the globe, changes to the environment have been linked to the increasing levels of disease. Road building in Latin America has been linked to increased incidences of leishmaniasis; gold mining has led to an increase in malaria resulting from water accumulation in pits and the edge effect has been widely linked to Lyme disease (Patz et al. 2004)

Whilst some diseases have been influenced by environmental change, others have been intrinsically linked to human activity. For example, a major source of rabies are animals that have become habituated to urban environments: Bats, scavenging racoons and feral dogs. Overfishing in Lake Malawi led to snail populations increasing exponentially, as did cases of schistosomiasis (Patz et al. 2004).

Applying One Health

As part of the One Health approach, land-use should be taken into account regarding public health policy, as changes in the environment influence disease spread. Instead of focusing on the disease as the specific issue, health policy should look at the entire picture. Animals often act as reservoirs for disease, and land-use and human activity affects those animals, and so by extension, the disease.

We can create a realistic risk assessment only by considering animal, human, and environmental health. This approach enables us to develop a sufficient response (Makenzie & Jeggo, 2019). It’s crucial to consider the environmental conditions of a specific location. These conditions can have wildly different influences on a disease. An irrigation scheme in India may cause an outbreak of malaria, but this may well not be the case in sub-Saharan Africa (Patz et al. 2004).

We also have to look at society’s actions that enable the spread and advancement of disease. The loss of large predators in fragmented habitats in the United States has led to an out-of-control rodent population (Patz et al. 2004).

There also steps that could be taken to mitigate the spread of disease. Flowering winter vegetation was observed to reduce spillover events of Hendra virus by drawing in hundreds of thousands of bats away from agricultural areas (Eby et al. 2023). Reintroducing snail-eating fish to Lake Malawi, would control aquatic snail populations and lower the presence of Schistosoma parasites.

References:

Eby, P., Peel, A. J., Hoegh, A., Madden, W., Giles, J. R., Hudson, P. J., & Plowright, R. K. (2023). Pathogen spillover driven by rapid changes in bat ecology. Nature, 613(7943), 340-344.

Mackenzie, J. S., & Jeggo, M. (2019). The one health approach—why is it so important?. Tropical medicine and infectious disease, 4(2), 88.

Patz, J. A., Daszak, P., Tabor, G. M., Aguirre, A. A., Pearl, M., Epstein, J., … & Working Group on Land Use Change Disease Emergence. (2004). Unhealthy landscapes: policy recommendations on land use change and infectious disease emergence. Environmental health perspectives, 112(10), 1092-1098.

Rabinowitz, P. M., Kock, R., Kachani, M., Kunkel, R., Thomas, J., Gilbert, J., … & Rubin, C. (2013). Toward proof of concept of a one health approach to disease prediction and control. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 19(12).